Health Equity in Action

Every small step makes a difference, and learning about what other groups are doing can inspire and motivate people to take action. Below are a few examples gathered in 2008 of promising initiatives happening on the community, state and metropolitan level.

Check back often as these will be updated regularly.

Access Plus Trust: Closing the

Black-White

Infant Mortality Gap!

South Madison Health & Family Center-- Harambee

A partnership between Head Start, Access Community Health Centers, the Madison Public Library, Planned Parenthood, and Public Health of Madison and Dane County

Madison, WI

http://www.smhfc-harambee.com/index.htm

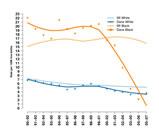

African American babies die before the age of one at two and a half times the rate of white babies. Their prospects are even worse in Wisconsin. According to Newsweek, “At 17.6 deaths per 1000 births Wisconsin’s infant mortality rate for African Americans is among the highest in the nation and is just below that of the Gaza Strip.”

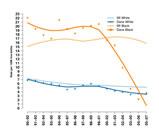

But Madison and the surrounding Dane County area lowered its overall infant mortality rate by 2/3 since 1990 (graph 1, above). More impressively, they became the first region in the nation to dramatically close the black-white infant mortality gap. For the 2002 - 2007 period, the Madison-Dane County infant mortality rate for African American babies had fallen to 6 per 1000 and for white babies to 4 per thousand. (According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control, the national infant mortality rate for Non-Hispanic White babies was 5.6 in 2006 compared to 13.4 for non-Hispanic Black babies).

But then in 2008, the Madison-Dane County African American infant mortality rate spiked. In 2009 it fell, but was still higher than the 2002-2007 rates. A statistical fluke? Or a new trend? That no one knows is not surprising, since most are still puzzled by what caused the fall in African American infant deaths in the first place.

“We don’t have a medical model to explain [the drop], says Dr. Philip M. Farrell, professor of pediatrics and former dean of the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, told The New York Times. Dr. Thomas Schlenker, the director of Public Health-Madison & Dane County, explains, “It’s a community effect. The decline in infant mortality is largely due to increasing numbers of black women who are able to carry their babies to term which is not explained by improvements in medical technology or changing demographics.”

A convergence of factors that seem to promote full-term delivery can be seen in the “one-stop shop,” South Madison Health & Family Center—Harambee, Swahili for "pulling together." Located in an old strip mall, Harambee pulls together the community by offering support, connections and a cluster of integrated services. In addition to clinical services and home visits by nurses, community residents can find legal help, assistance locating jobs and housing, nutrition classes, a library and other supports including a Head Start program. Perhaps most of all, they feel valued. At the Harambee-based programs, women report feeling respected and cared for.

“What is different in Dane County, says Madison’s former mayor, Paul Soglin, “… is that here a 19- or 25-year-old black woman finds a [medical] facility that is not the white man's institution—it's hers."

Some other one-stop community centers responsive to the overall needs of their communities and which provide more than pre-natal care have reported similar results. The Developing Families Birth Center (DFBC) in Washington DC, for example, reported pre-term births among the African American women they serve at close to 5% in 2006 compared to 15% in the city at large. According to founder Ruth Lubic, the DFBC doesn’t view infant mortality as a medical condition but a social condition with medical consequences.

Infant mortality rates, according to a report by the Centers for Disease Control studying the Madison results, "reflect the health of infants, their mothers, their families, and the communities into which they are born and are universally recognized as key indicators of the health of populations."

Harambee was made possible by an unusual level of cooperation among public and private local health care systems, the public health department, and private, non-profit, and charitable organizations dedicated to improving health outcomes for pregnant women and their families. Mayor Paul Soglin describes the social and medical situation in Madison as simply “Access plus trust.” Harambee’s inception during the late 1990s coincided with a conscious decision by local hospitals and primary care systems not to compete over pregnant women with the most lucrative private insurance coverage. Instead, they agreed to cooperate to ensure that all women regardless of economic, racial, cultural and language barriers received excellent prenatal care.

Obviously, Harambee was not the only reason for the decline in African American infant mortality. But it does appear to be an important one. Perhaps more valuable than ensuring access to quality care, Harambee offers holistic support to women and their families. In this case, trust encompasses a variety of factors that mitigate racism in clinical settings. Lorraine Lathen, President of Jump at the Sun Consultants, Inc., and a technical consultant to the State of Wisconsin in their Healthy Births Initiative reports that in other parts of the state some black women report feeling “pre-judged”—one mother [in an excerpt from “Place Matters: The Decline of Infant Mortality in Dane County” a locally produced documentary on the issue] said that “it might surprise people that black women ‘do have families,’ and that the father of her child, for example, is her husband, not ‘my baby daddy’.”

So, why the sudden rise in infant deaths in 2008? Was it just a statistical fluke, or did something change? The recession? The University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health has begun an investigation. Stay tuned.

Madison & Dane County’s work has also been covered by The New York Times and Newsweek

Building Trust by Installing Streetlights?

West Wabasso PACE-EH Project Assessment

Indian River County Health Department

Vero Beach, FL

In 2004, the 350-resident community of West Wabasso, Florida, where the median household income is less than $6,250 a year, lacked streetlights, sidewalks, connections to the county sewer, and clean drinking water. Residents routinely cooked, drank, and bathed in brown water. When county health official Julianne Price first approached the West Wabasso Civic League about working on health and infrastructure needs she encountered skepticism if not outright distrust. Many members of the League had seen well-intentioned county officials try (and fail) to bring any meaningful change to the community.

Price persisted and used the Protocol for Assessing Community Excellence in Environmental Health (PACE EH) to determine the environmental health needs of residents. This protocol emphasizes spending time in the community and really listening to residents’ needs. Although Price helped facilitate the process, ultimately the community set the project’s priorities. Despite their substandard housing and brown water, residents identified street lights as the major problem facing their community. By quickly meeting the community’s number one need (in just seven months!) the department earned the community’s trust. This early victory built the Civic League’s confidence around both the project and the county officials.

As the community’s goals became more ambitious they worked hard to publicize their situation. To gain support from local and state politicians the health department, in cooperation with residents, lead bus tours through Wabasso. They invited legislative aids, county officials, and others on these tours to witness the poor condition of even basic infrastructure. In addition, neighborhood groups met with representatives from the police force, parks and recreation department, and the county commission to identify achievable solutions to the community’s problems. These conversations not only brought about important infrastructure work, they also improved the relationship between this under-served community and the county government. After the project 91% of residents reported feeling more able to work with local agencies to bring positive change to their neighborhood.

The holistic solutions that the health department facilitated, which involved the health department, urban planners, and representatives from government and private agencies, marshaled the county’s diverse resources. Price teamed up with local agencies to leverage the seed money at her disposal by soliciting donations, waving landfill fees, and negotiating reduced rates from contractors. In just three years the Indian River County Health Department’s PACE EH process yielded sidewalks, a walking trail, fitness equipment, a potable water system, repaired septic systems, built a house, repaired 28 homes, demolished 8 abandoned homes, and installed streetlights. Residents reported that the police department has improved its work in their neighborhood. Residents also use more public transit, exercise more frequently, and sense an overall improvement in their quality of life.

The project’s major contribution to the community, however, may be the sense of empowerment it catalyzed. Today, the community’s Civic League continues to work toward changes it has identified through a visioning process. These resident-leaders approach city and county officials about their needs and nurture the growing sense of community pride in West Wabasso. Price happily reports that the health department now attends meetings only in a passive, advisory role. With the health department’s help leveraging a small, $30,000 grant into over $1.5 million dollars of infrastructure improvement and several months of community dialogue West Wabasso improved their community and their ability to work press government and private enterprises for change.

Download the project assessment in the Journal of Environmental Health.

Small Grants, Big Discussions

Healthy Communities Initiative

The Health Trust, Campbell, CA

healthtrust.org

In spring of 2008, The Health Trust, a Silicon-Valley-based foundation, launched the Healthy Communities Initiative by offering small $1500 grants to local organizations to screen and discuss UNNATURAL CAUSES. The initiative focuses on reducing and eliminating health inequities, with the ultimate objective "to make Silicon Valley the healthiest region for all its residents no matter their race, ethnicity, income level, or neighborhood."

Forty diverse organizations completed received screening grants and initial findings highlight some useful lessons:

• Simple is best. The application for potential grantees was brief and straightforward, making it easier for organizations that do not usually apply for Health Trust grants to get involved. Subsequently, participants represented a broad spectrum of affiliations, including education, community residents, health, social services, faith-based, housing, and government.

• Partnerships are key. The Health Trust partnered with the Santa Clara Public Health Department and San Jose State University to engage the community in discussions. When they found that the majority of participants were eager to participate in local action, the trust partnered with the local grassroots interfaith organization People Acting in Community Together to develop plans for future community action.

• Trained facilitators are essential. The quality of discussions varied depending on the skill of the facilitators, who were helped by not adequately prepared by the toolkits. The trust reflects that they could have taken a more active role in coordinating training.

• Participants will want next steps. Be ready for them! The Health Trust had already planned to hold a 2009 Health Equity Summit for grantees and others from the region. In response to participant demand, the summit will now include a community action planning component.

Download the grants report.

From Community Screenings to Grassroots Action

Great Start Collaborative and Partners

Kalamazoo County, MI

tinyurl.com/6co2gh

For years Dr. Arthur James, obstetrician and gynecologist in Kalamazoo, Michigan, has worked tirelessly to spread the message about social determinants of health, but the framework has not been widely understood or acted on in the county.

So when Jacque Eatmon, director of the Kalamazoo County Great Start Collaborative, saw UNNATURAL CAUSES on PBS in spring 2008, she recognized its utility and quickly called Dr. James and other colleagues to start using the series as a community education tool.

Together with Kalamazoo United Way’s Strong Families/Safe Children program, the Collaborative soon launched a health equity community watch—a widespread screening and mobilization campaign. It started with one screening that brought thirty representatives from social groups, faith-based organizations, nonprofits, and businesses. From there attendees quickly volunteered to host their own events.

The Collaborative lends out copies of the DVD, offers facilitator support, and provides resource packets from materials in the UNNATURAL CAUSES Action Center supplemented with regional information on infant mortality and health inequities. The libraries purchased copies of the series for use by the general public, and county organizations now circulate multiple DVDs for a variety of internal and public screenings:

• The community watch has held screenings and discussions for diverse groups, including parents, college students, unemployed community members, recovering substance abusers, community leaders, and local politicians.

• The newly-resurrected Inclusion and Diversity Division of the county’s intermediate school districts is organizing screenings for district administrators and teachers.

• The health department hosts regular, frequent viewing sessions for its staff.

• One church is showing the series weekly during October 2008, and many others have shown portions.

• Board members have brought the series to a variety of events, including a 4000 person "ultimate family reunion" where twenty people took time off from the party to watch and discuss "When the Bough Breaks."

The community watch, extended to January 2009 due to popular demand, is only the first phase of the Collaborative’s current strategy. In early 2009, the project will review the community discussions and draw up recommendations for next steps. Key players from different sectors will then come together in a community summit to develop a countywide health equity action plan.

Pediatrician Dr. Janice James, discussion leader and ally of the initiative, stressed the need to work with directly with community members when developing any action plan: "Everyone has good ideas; sometimes those worst affected [by inequities] have the best ideas, though they tend to be ignored." Community watch attendees have already put forward an immediate objective: improved zoning, a locally-determined policy issue with easily understood, tangible results.

It Takes a Village to Raise a Child – A Comprehensive Approach

Harlem Children’s Zone Project

New York, NY

www.hcz.org

The Harlem Children's Zone (HCZ) is a pioneering community-based organization that works to enhance the quality of life for more than 8,600 children and families within a 100-block area of Central Harlem in New York City.

The HCZ Project uses a multi-pronged approach to provide integrated services and support in areas that directly impact health: parenting/child development, nutrition and fitness, education, housing, economic opportunity, and employment.

The HCZ Project includes two early childhood intervention programs: The Baby College, which addresses the needs of children between the ages of 0 to 3 and their parents; and Harlem Gems, a universal pre-kindergarten program for four-year-olds. HCZ also runs its Asthma Initiative, in partnership with local hospitals and public health agencies, which screens all neighborhood children for asthma and helps combat triggers. Workers conduct home visits to survey families and to help provide a full range of environmental, social, educational and medical interventions when indicated.

For older kids, HCZ operates the Promise Academy, a charter school for middle- and high-school students that includes a free health clinic, a cafeteria with nutritious food, and programs and services to screen and combat obesity, asthma and diabetes, among other ailments. HCZ also helps place over 90 AmeriCorps-funded Peacemakers at local public elementary schools, where they help run classroom, after-school, and summer enrichment programs.

The HCZ Project also offers a range of other youth-oriented programs, including: TRUCE, a comprehensive development program for high-school students, focused on academic growth and career readiness; Investment Camp, a financial literacy program; the Employment and Technology Center, which provides training, support and job placement; and a community garden and food distribution network managed and run by youth.

HCZ also works to help families by advocating for policy changes at the local and state level. HCZ officers are active on several economic and childhood advisory boards, and the HCZ Practitioners Institute helps educate participants about best practices, successful programs, and the need for a comprehensive approach to building a healthy neighborhood and strong community.

Investing in Better Health

The Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Minnesota Foundation

The Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Minnesota Foundation

St. Paul, Minnesota

www.bcbsmnfoundation.org

The Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Minnesota Foundation (BCBSMNF) is the philanthropic arm of the largest non-profit health plan in Minnesota. The foundation takes a broad view of health, one that focuses on factors beyond health care, genes and lifestyle. Its funding targets “upstream” initiatives – such as those that promote social connectedness, environmental quality, early childhood development, and safe, affordable housing - to improve the health of all Minnesotans.

For example, Healthy Together: Creating Community with New Americans is a statewide effort to reduce health inequities among immigrants by fostering exchanges and interactions between newcomers and established community members; strengthening the organizational capacity of groups serving refugee and immigrant populations; and providing social support and mental health services to new arrivals. The Latino Support Committee in Blackduck, Minnesota, and the Hmong American Partnership project are examples of groups funded under this initiative.

A related foundation focus is Growing Up Healthy: Kids and Communities, which helps communities work across sectors in new ways to create an environment that nurtures the health growth of children under the age of five. This program area funds projects in which health and two or more of the following intersect: early childhood development; safe, affordable housing; and the physical environment. For example, the foundation gave $20,000 to the Minnesota Environmental Initiative to retrofit Head Start buses to reduce diesel emissions in Washington and Anoka Counties; it also funded the North American Water Office to document how pollution threatens the health of indigenous people who depend on fish as their primary food, and to improve early developmental, educational and health outcomes for native children on the White Earth reservation through the Indigenous Women’s Mercury investigation.

In addition to funding programs, the foundation advocates for public policies that ensure universal access to quality health care and increase “upstream” conditions for health. Through the National Conference of State Legislatures, for example, the foundation has brought together legislators and agency representatives with refugee and immigrant leaders to identify challenges and develop policy solutions for more effective immigrant integration and healthy communities, and the Leadership Institute continues to develop and recognize community leaders who effectively address the connections between health and social, environmental and economic issues.

A Broad-based Strategic Plan for “America’s Healthiest Community”

Metro Denver Health and Wellness Commission

Metro Denver Health and Wellness Commission

Denver, CO

http://www.mdhwc.org

The mission of the Metro Denver Health and Wellness Commission (MDHWC) is two-fold: to maintain Colorado’s reputation as the nation’s healthiest population by combating its trend towards obesity and inactivity and to develop interest in health and wellness as a way to boost regional economic growth, increase productivity and lower health care costs. Comprised of key stakeholders from metro area cities, including health care providers, community leaders, policy makers and representatives from business, education, and philanthropy, the commission is a broad coalition of groups uniquely positioned to make a difference in the health of the region.

The MDHWC’s recently released strategic plan outlines three major priority areas: Healthy Schools/Early Childhood Development, Healthy Worksites, and Healthy Communities. In addition, the commission’s first annual Health of the Region Report lists the metrics for measuring the effectiveness of MDHWC initiatives in upcoming years.

Among the recommendations included in its strategic plan, the MDHWC suggests that local schools offer opportunities for physical education, nutrition classes and healthy food to improve test scores and concentration, reduce incidences of disruptive behavior and absenteeism, and lower depression. The plan also suggests that worksite wellness programs and incentives for healthier behavior can benefit both employees and employers through lower rates of absenteeism, improved safety and morale, and lower health care costs. Finally, the commission advocates the development of a regional transportation system that supports physical activity, decreases pollution and traffic congestion, and improves access to parks, trails, and healthy foods.

The key to the commission’s success so far has been its ability to attract and engage diverse representatives across many sectors. The involvement of government, non-profit and business leaders – including local mayors, foundation and industry executives, school district employees, consumer health advocates, and groups that serve and represent low-income communities and communities of color – has ensured buy-in, resources, and support for the commission’s recommendations. Moreover, the commission’s message that improving health conditions is a win-win situation resonates among all groups.

Integrating Health Equity into County Programs and Services

King County Equity and Social Justice Initiative

Seattle, WA

www.kingcounty.gov/equity

The King County Equity and Social Justice Initiative takes aim at long-standing and persistent local inequities and injustices.

"It is unacceptable that your skin color or your home address are good predictors of whether you will have a low birth weight baby, die from diabetes or your children will graduate from high school or end up in jail," says King County Executive Ron Sims. “Government and local communities are better prepared than ever before to address these challenges.”

The Initiative, launched in early 2008, works on three levels:

1. Delivery of King County services: All King County departments have committed to specific actions to promote equity in 2008. For example, the Department of Development and Environmental Services will review and revise comprehensive plan policies to encourage vibrant, mixed-use neighborhoods that are diverse and integrated. The Transportation Department will prioritize creating transit-oriented developments with close proximity to affordable housing, recreation and employment centers.

2. Policy development and decision-making: King County will ensure that promoting equity is intentionally considered in the development and implementation of key policies and programs and in making funding decisions. The county is developing and testing an equity impact assessment and review tool, and it will incorporate use of this tool in decision-making processes.

3. Community partnerships: Key opportunities to promote equity and social justice go beyond the boundaries of the government, and King County is committed to listening to community voices. The county is collaborating with partners from many sectors in the areas of community engagement and education. King County has an opportunity to address the historical lack of access to decision-making by involving community members in developing solutions to inequities.

Community Organizing and Environmental Justice – Fighting for Health Equity

Asian Pacific Environmental Network

Asian Pacific Environmental Network

Oakland, CA

www.apen4ej.org

The Asian Pacific Environmental Network (APEN) envisions a world where "all people have a right to a clean and healthy environment in which their communities can live, work, learn, play, and thrive."

Communities of color bear a disproportionate amount of the nation’s environmental problems from polluting facilities and diesel truck emissions to toxic work places. At APEN, we organize for environmental justice and healthy environments by empowering low-income Asian Pacific Islander communities to build political strength and make decisions that affect their lives.

Developing the leadership of our grassroots members and organizing the community into a powerful voice is the heart of our work. APEN has two organizing projects: Power in Asians Organizing in Oakland, California, and Laotian Organizing Project in Richmond, California, which was featured in the “Place Matters” episode of Unnatural Causes.

APEN member and leader Khamphay Phahongchanh lives in Richmond and has been a member of the Laotian Organizing Project (LOP) for nine years. He is part of a large Laotian community in Richmond who were resettled here in the aftermath of the Vietnam War. He became involved after a major industrial accident at the Richmond Chevron oil refinery hospitalized thousands of people in 1999. "I went to the LOP office for a community meeting where there were many diverse Laotians in the meeting: young, old, and all from different Laotian tribes. After the meeting, I thought about what could be done about this problem and I became more interested in LOP."

Khamphay and LOP successfully organized to win the nation’s first multilingual emergency warning system. He believes LOP’s work is important because it brings people together to fight for their rights.

To learn more about Khamphay, LOP, and APEN, visit www.apen4ej.org.